Being a video producer during a pandemic has been strange and challenging because what often makes this work special is done in person. The bread and butter of our work is communication, connection, and camaraderie. It’s that run-and-gun, in-the-field, heart-to-heart production (known as “docu-style” video), where the IRL magic really happens.

Many projects call for a documentary sensibility. Even a campaign launch video or a piece of branded content can be approached through a documentarian’s lens. Capturing unchoreographed, spontaneous moments of life give authenticity and honesty to any video — whether it’s 30 seconds, two minutes, or dozens of hours (aka Ken Burns-style).

So — how do you approach telling someone else’s story? There are a lot of little things that help the process: doing your research, preparing questions, bringing a script. There’s power in sitting down with another human being, listening to their story, and sharing that with the world. But at its core, it’s all about building trust.

The interview before the interview

Our goal is always to help our subjects find their voice and uplift their stories with beautiful cinematography and succinct editing. When documenting or profiling someone who might not have camera experience, it’s a balancing act of getting the shots and soundbites you need to craft a compelling narrative, while still creating a comfortable, judgment-free space that doesn’t overwhelm or intimidate.

When there’s time, a phone conversation ahead of the formal interview is helpful for building rapport and combing through the story to identify the key beats you want to hit when the cameras are rolling. This was especially important in this piece about criminal justice reform. Our campaign organizing staff was able to put me in touch with Bridgette, a survivor of domestic abuse and a formerly incarcerated activist, but I had only one day to make contact and set up an interview while we were in town. We connected the night before our interview, and Bridgette was extremely generous with her story.

Being able to just talk together as people, without the added pressure of cameras, was essential to build basic trust and get to know her. It was also important to identify how much Bridgette was comfortable sharing prior to filming. This kind of “pre-interviewing” has helped us in other projects, like this interview on the segregation of our public schools.

Setting “the mood”

An interview is part therapy, part public speaking, so you want to create the right conditions to give space to both of these (often contradictory) elements at once. My go-to directing mantras are: “you can always start over” and “editing is magic!” Editors might fight me on this one, but encouraging the person in the hot seat to speak freely lightens the mood. Putting people at ease by invoking the powers of *movie magic* can change the energy of someone’s delivery.

If I’m trying to get a specific soundbite, or want someone to repeat something, I use words of affirmation. Something like — “I love when you said ‘xyz’ a minute ago, that was a fantastic point. Can you start there and elaborate?” Otherwise, people say something amazing, but often trail off, losing confidence and making for a trickier edit.

Techniques like this helped in our interview of a working mother dealing with student loan debt, and in this portrait of an Oklahoma school teacher discussing how our public schools shape us.

When it comes to finding the shot, keep it minimal, especially when filming in people’s homes. Coming in hot with a ton of gear tends to freak out camera-shy folks. Find a space with a nice backdrop and plenty of natural light to set up the shot, supplementing with a light or two.

When working with a crew, it’s helpful to collaborate with a cinematographer who brings a relaxed energy to set and the soft skills to go along with the technical side of the job. Having someone you can communicate with more easily in a sensitive moment is truly a lifesaver.

Out in the wild

Interviews in the field are a different story. This is where preparation, curiosity, and flexibility all come in handy — you don’t have the luxury of control in these settings.

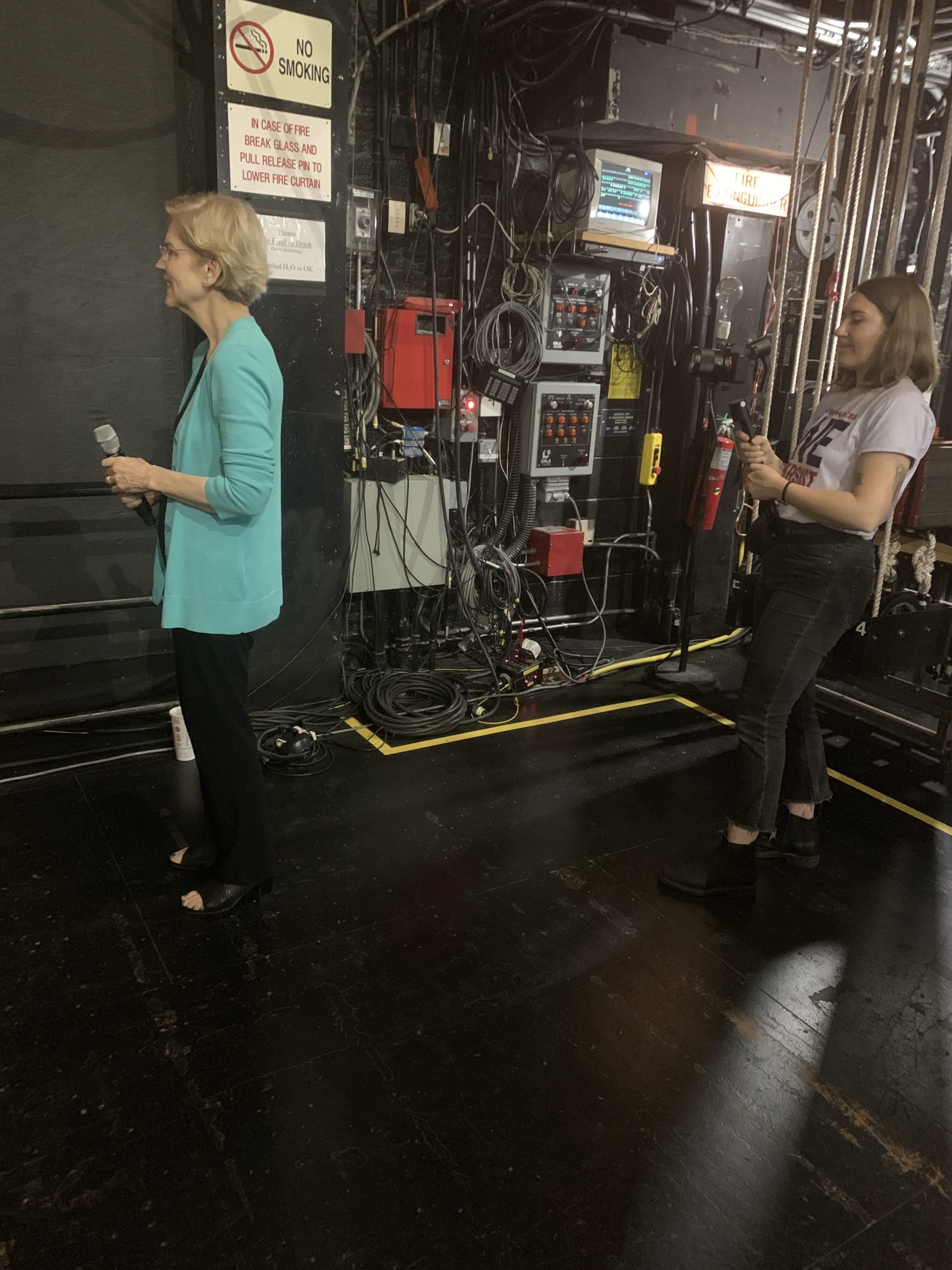

When our team documented Elizabeth Warren’s walkthrough of Black Wall Street, we did our research and came prepared. Our interview with the Reverend Dr. Turner was completely unplanned, but when the opportunity presented itself, we were ready and informed. Knowing that this shoot would require ample time and space to listen and learn, we padded our schedule with as much time as possible around this stop. It was our best interview of the day, and a deeply rewarding moment, especially given the pace of our work on the campaign.

When shooting in the field (rather than a controlled setting like a sit-down interview), staying nimble and traveling light is key. More often than not, video producers are a one-woman show so when we’re working alone, we throw our cameras on a monopod, pop a shotgun mic on, and pray for quiet. We make the best of our circumstances, using our position within a space to maneuver the frame and create the best “mise-en-scene” possible.

A particularly chaotic shoot in the field was at a United Auto Workers strike. It was crowded and our schedule was tight. What made us successful was having a plan, but also being nimble and spontaneous. After our team captured the event and Senator Warren’s remarks, I took my camera off my rig to capture some handheld interviews with strikers. It was the perfect opportunity to capture the spontaneity and incredible enthusiasm of the day’s events — and we seized it.

When all these elements combine — a compelling story, a connection with your interviewee, a comforting space, and a well-composed shot — you can really feel the magic of the medium kindle and spark. It’s hard not to get a little addicted to the process.

Sometimes, I’ll hear from people I’ve interviewed months or years ago, and that says to me that it’s been a meaningful exchange for both of us. That we built something together. My team isn’t just there to capture or “take” something — as the photographic term might imply. Rather, the goal is to give something to my interviewees, too. Maybe that’s clarity, reverence, resolution — or just a little boost of excitement and confidence that getting in front of a camera and speaking your truth can give.

These days, I’m especially nostalgic for it. But the distance and isolation has also made me more grateful for these experiences, and all the exciting learning opportunities I have to look forward to when I’m back in the field.

Want to learn more about our video practice? Get in touch.